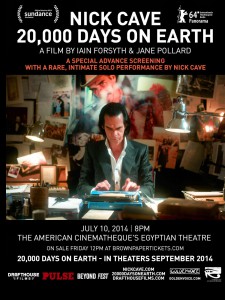

At a special screening at The Astor, the Nick Cave documentary 20 000 Days on Earth was screened, with Nick present for a Q&A session afterwards. The film, directed by Iain Forsyth and Jane Pollard, loosely depicts the lead up to the production and performance of Push the Sky Away, the fifteenth studio album of Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds, who had just completed an Australia and New Zealand sixteen venue tour, with several shows added to cater for excessive demand.

At a special screening at The Astor, the Nick Cave documentary 20 000 Days on Earth was screened, with Nick present for a Q&A session afterwards. The film, directed by Iain Forsyth and Jane Pollard, loosely depicts the lead up to the production and performance of Push the Sky Away, the fifteenth studio album of Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds, who had just completed an Australia and New Zealand sixteen venue tour, with several shows added to cater for excessive demand.

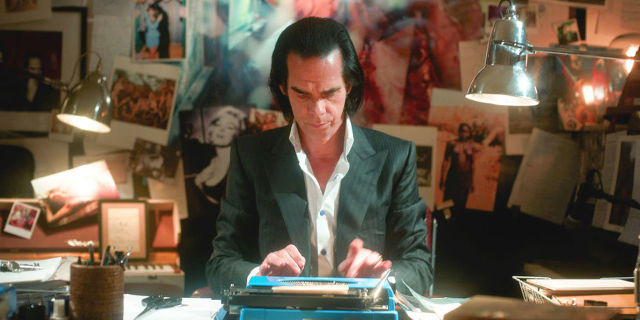

The real quality of the film however, is not the production process of the album, but the contrived scenes of reminiscence and introspection. There is an insight into the psyche of Nick Cave with an interview with a psychoanalyst (a real one, Darian Leader, it’s worth mentioning) and a succession of interviews and conversations with various people he’s worked with, including Ray Winstone, Blixa Bargeld, and Kylie Minogue. These characters, to use a fairly transparent metaphor, appear in a car with Nick, being part of his journey. Naturally enough, as it’s his journey, he’s in the driver’s seat. Also featuring quite heavily in the film is long term collaborator, Warren Ellis. These interviews and conversations are well-supplemented throughout the film by rapid montages used for the rapid succession of time, ideas, and experiences, the baroque richness of studio and home environments, and with some expressively quiet moments, such as the final scene as Cave stands on the beach in his now-hometown Brighton.

The film really illustrates the thinking process of Cave in his aristic production, especially the process of memory, by which he describes it as the most important part of a person, noting the process of imperfection, editing, and mythologising of the self. He also describes the idea of losing one’s memory as the most terrifying fear to him, which matches quite well wth Minogue’s concern in the film of loneliness and being forgotten. The element of narcissistic, almost impossible to avoid in the celebrity, is evident here. The vocalist expresses themselves to the audience in the hope that they can impart their memory to others with a desire for greater permanence, even as they provide a particular expressive stage presence that is made for the audience. The author will also confess to a little bit of delight when Cave described quite accurately the importance of counterpoint in the construction or development of lyrics, alhough a description of thematic harmony was absent. There were moments of clever humour, but unusually few of great sadness and oddly, almost no discussion of his mother.

The Q&A session itself allowed for further elaborations on these theme. Cave quickly dealt with some of the more daft questions (“Do you have a garden?” “No”, “Why do all your bands start with ‘B’?” “Grinderman”, “There wasn’t much about Blixa” “He was in the fucking film” etc), and gave insight in the more challenging ones. When asked on his special talent, he made the point of his one-eyed determination to see an artistic idea through, which he felt that even artists better than him may have lacked. He gave accolades to people like Roland S. Howard, and expressed his opinion that he was glad to discover on his visit that “Fitzroy Street is shithole again” (I thankfully resisted the urge to shout, “Did you score?”). Apropos, he also elaborated on the peculiarity of Australia; the heat, the harshness of the light, and the cultural irreverence which would often make Australian’s feel a bit alien in other parts of the world. With a couple of leading questions, a youthful experience also provided the audience with what many may have already guessed – the pivotal experience in Nick Cave’s life that led him to music – was hearing Leonard Cohen‘s ‘Songs of Love and Hate’ in his early teenaged years. It is perhaps on that realisation, that Cave is following very much in these footsteps, and that truly great music can set the direction of a person’s life.

Leave a Reply