- Stephen Witt: How Music Got Free: The End of an Industry, the Turn of the Century, and the Patient Zero of Piracy (Vintage, 2015/2016 — UK, US)

How Music Got Free purports to be the story of the last twenty years of the record industry, Witt having been one of the kids who collected MP3s in his college dorm just before Napster. It isn’t the story of the MP3 revolution, but it is some stories, only one of which is seriously important to the claim in the subtitle: “the end of an industry, the turn of the century, and the patient zero of piracy.” But the details mostly aren’t wrong.

The threads are the warez scene pirates, who were leaking stuff before release (Dell Glover of Rabid Neurosis/RNS, who worked in PolyGram’s CD plant in North Carolina); Doug Morris, storied record industry executive, who made a fortune at Universal in the 2000s selling rap, even as the record industry slowly burned; and Karlheinz Brandenburg, inventor of MP3 at Fraunhofer.

The threads are the warez scene pirates, who were leaking stuff before release (Dell Glover of Rabid Neurosis/RNS, who worked in PolyGram’s CD plant in North Carolina); Doug Morris, storied record industry executive, who made a fortune at Universal in the 2000s selling rap, even as the record industry slowly burned; and Karlheinz Brandenburg, inventor of MP3 at Fraunhofer.

It’s written in the incredibly irritating novel-structured style that seems standard these days for nonfiction accounts of recent events. The strained descriptions of the players as if they’re fictional characters. Literary foreshadowing that makes me go “yes, but why are you telling me all of this” — this is not a novel and you are setting up plot threads like it is.

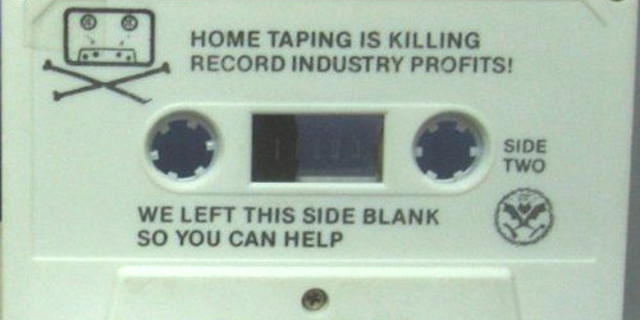

Real lives of real people do not happen in stories, and history may happen as ridiculous contingency — shit happening, which does make good anecdotes — but it’s shaped by material forces. The Great Man theory of history is largely incorrect. In this case, the material forces were: 1. computers; 2. the Internet; 3. Moore’s Law applied to hard disk size; 4. lossy psychoacoustic compression. The book even notes how, the moment MP3 works even a bit, people immediately realise the record industry is now fucked.

Brandenburg is a genius who did amazing work on lossy compression — and after MP3 he invented AAC, as used in iTunes — but the Fraunhofer team was far from the only player. MPEG-1 Layer III was not a development from MPEG-1 Layer II, but its technically superior competitor that lost the political game for industry support, which is why MP2 is in DVD and DAB and Freeview. Even after this loss, contingency — shit happening — meant that, through the warez scene, the promotional shareware Fraunhofer MP3 encoder and player took on a life of their own and the new young Internet users flocked to the format. But if they hadn’t, MP2 lossy compression would have taken much the same role.

Once we have computers, hard disks and Internet, we can record at home and distribute the files. Lossy compression helps greatly. Or, per this depiction of the thoughts of Doug Morris, which is probably the most important paragraph of the book and it’s thrown in as an aside:

And, really, what could he have done differently? If there was some other record industry executive who’d done better, who’d taken a different path, maybe the case could be made. But the decline of the music industry had affected every player, from the largest corporate labels to the smallest indie. Morris had once been a gatekeeper, the guy you needed to get past to get into the professional music studio, and the pressing plant, and the distribution network. But you didn’t need any of that stuff anymore. The studio was Pro Tools, the pressing plant was an mp3 encoder, and the distribution network was a torrent tracker. The entire industry could be run off a laptop.

Or, as I’ve put it repeatedly: the record industry is fucked because they no longer control the means of production, they no longer control the means of distribution and the marginal cost of distribution is about zero.

I remember my own moment of realisation that the record industry was fucked, when my then-girlfriend and I went to visit her friends in Adelaide in late 1998 and they were swapping burnt CDs over beers in the back yard of an evening.

I was slow on the uptake; I should have realised when I was on the Severed Heads mailing list in 1995 and 1996 and Tom Ellard was putting together Severything, his complete works CD encoded in MP2. (Because MP3 hadn’t happened to win with the college kids as yet.)

I got occasional calls from Napster users when I was doing dialup Internet tech support in 1999 and 2000. (I think we just told them they bought a service and we weren’t blocking anything.) I didn’t download my first mp3 until 2000, some J-Pop thing I still remember the chorus from. I played it on the 75MHz Compaq work laptop that came with my new job as a sysadmin. My housemate had a server full of MP3s (as you do) from which I played VNV Nation’s Empires for the first time, leading into my present addiction to bleepy EBM synthpop. (“Ohhh, all that stuff Jus’s playing around the corner at Blue Velvet!”)

I later bought a gigantic 40GB hard disk just to rip my CDs to MP3, so I could have my own collection on a 1000-disc changer. And it was bloody revelatory and I lost all interest in non-digital music at that moment. I literally don’t understand why people buy CDs and LPs and seven-inches any more. As the author puts it:

Compact discs got scratched and cracked and stolen at parties, but an mp3 was forever. The only advantage the compact disc offered, therefore, was the tactile satisfaction of physical ownership. At Universal, packaging was all they were really selling.

The book does detail everyone realising over and over how obviously fucked the record industry was just from material forces, except the record companies themselves. Their utter ineptitude in the face of the fire that was about to consume them beggars belief. PressPlay was considered too stupid to be real, surely it was some sort of legal game or conspiracy. No, the book sets out: it really was just blithering stupidity. An awful product with added technology, in response to the problem of people not wanting their previous awful product.

Remember the record industry suing downloaders directly in their jawdroppingly bullying “educational lawsuits”? Hilary Rosen actually refused to be the face of it and quit the RIAA. “Dissenting was Roger Ames, the head of Warner Music Group, who argued that suing one’s own potential customers was unlikely to result in long-term profitability.” Ya think?

I’m unconvinced the historical threads chosen for this book quite explain the material forces at play. The overwhelmingly most important story here is that of Brandenburg, Fraunhofer and MP3; Brandenburg has won and MP3 has taken over the world by the end of Chapter 10, halfway through the book. I’m utterly unconvinced the warez scene was as big a player as Witt implies by the amount of coverage; the fact of free music was I think vastly more important than the details of big rap albums being leaked. (So Oink and the Pirate Bay, not RNS.) Doug Morris’s story is actually really interesting (THIS MAN HAS RUN EVERY MAJOR), and, as he argues, he did about as well as anyone could be expected to with what he was up against; but in terms of the historical forces the book claims to be about, he’s a replaceable cog.

So it founders in the vast reaches of the “why are you telling me all of this” middle, but seems to resolve its few threads okay by the end. As someone who was there and watching the details closely for most of the two decades it covers, I’d question its focus, but I’d say it doesn’t get much wrong, and that itself is quite the blessing. Read it for the story of the rise of MP3.

Leave a Reply