“No one would have believed, in the year 2020 of the common era, that human affairs were about to be disrupted by a global pandemic at in a time when great powers of the Anglosphere were governed by those most incompetent and most indifferent to the health and lives of their citizens; as people pleaded to have their affairs changed so that they could live and have security, those in power gave them the choice of income with death, or poverty and austerity, all with the care that a man with a microscope might scrutinize the transient creatures that swarm and multiply in a drop of water. With infinite complacency, these men went to and fro over this globe accumulating wealth and power, serene in their assurance of their empire over the planet. Across this gulf of space, the hearts that immeasurably more selfish than ours, their intellects small, poisoned, and unsympathetic, regarded this earth with envious eyes, and slowly and surely drew their plans against us.”

“No one would have believed, in the year 2020 of the common era, that human affairs were about to be disrupted by a global pandemic at in a time when great powers of the Anglosphere were governed by those most incompetent and most indifferent to the health and lives of their citizens; as people pleaded to have their affairs changed so that they could live and have security, those in power gave them the choice of income with death, or poverty and austerity, all with the care that a man with a microscope might scrutinize the transient creatures that swarm and multiply in a drop of water. With infinite complacency, these men went to and fro over this globe accumulating wealth and power, serene in their assurance of their empire over the planet. Across this gulf of space, the hearts that immeasurably more selfish than ours, their intellects small, poisoned, and unsympathetic, regarded this earth with envious eyes, and slowly and surely drew their plans against us.”Is it not the most appropriate time to consider the great disaster story The War of the Worlds, as a pandemic continues to sweep the globe, with no end in sight? Before delving into this famous work and its successors, mention must be made of H.G. Wells himself, an astoundingly prolific English writer who lived from 1866 to 1946, with origins as a fairly poor family who required donations from his cricket skills as a source of income. A broken leg led to an immersion in literature and then a career in teaching and writing. He was a person who incredible prescience he foresaw the development of a variety of technologies in advance of their actual implementation, most famously nuclear weapons in The World Set Free (1914), coupled with an ability to present history in a concise form, The Outline of History (1920), and A Short History of the World (1922) both of which had enormous impact and recommended by Albert Einstein. His debut famous science fiction novels (then called “scientific romances”) novel was The Time Machine (1895), then The Island of Doctor Moreau (1896), The Invisible Man (1897), The War of the Worlds (1898), and The War in the Air (1907). An evolutionary biologist by training, politically a socialist, and, suffering from the illness, founder of The Diabetes Society in 1934. He was nominated for a Nobel Prize in Literature four times, but never won, which is a curse of science fiction writers.

The Book (1887)

The book is, through contemporary eyes is, in many ways, somewhat curious. As was the fashion at the time, it was serialised in 1887 which accounts for the rather delightful cliffhanger style at the end of each chapter, but also for its relative verbosity. It is also notable for being, as they called it then, a “scientific romance” (which would include the writing of Wells, Jules Verne, and Arthur Conan Doyle), rather than “science fiction” as we would call it today, perhaps a key difference that a scientific romance is more of a fiction that is scientifically informed, rather than the more fantastical speculations that are often applied with the phrase science fiction. This said, there is plenty in The War of the Worlds that is completely wrong scientifically, but it did make use of what was at least erroneously considered plausible at the time. One could perhaps accurately describe significant portions of late-twentieth-century cyberpunk novels as scientific romances under this consideration.

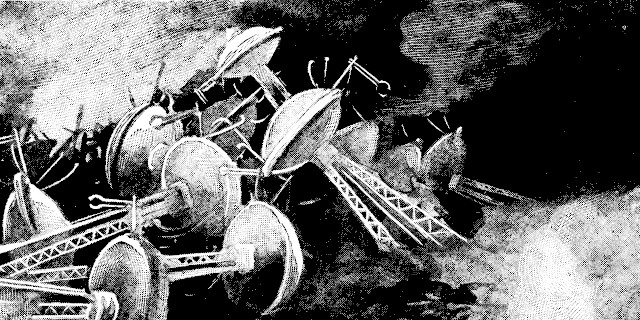

The nineteen chapters, available on Wikisource, that make up the story describe, from a narrator’s point of view (with very little elaboration on characterisation), how various explosions are noted on the surface of Mars, which later are revealed to be an invasion force armed with deadly heat-rays and poison gas which easily overcome human resistance (with some minor exceptions, including the valiant charge of the HMS Thunder Child), leading to military and civilian rout, including being separated from his wife. The narrator takes refuge with a mad curate as Martian machines start collecting people for their own nourishment. Making their escape, the Narrator discovers that the Martians are refoliating the earth with their “red weed, and re-encounters an artilleryman from the initial invasion force, who has a grand plan to rebuild civilisation but is too lazy to carry it out. Eventually, driven mad from the accumulated traumas, the narrator in a deserted London discovers that the Martians have succumbed to Earth’s microbes. Eventually, he is nursed back to health and reunited with his wife.

Wells explicitly stated that a motivation was the imperialist British invasion of Tasmania, the establishment of a colony, and the effects on the indigenous population. Apart from using what was acceptable scientific theories at the time concerning Mars and interests in alien life, especially suppositions on the age of planetary formation etc. In a prescient manner, the book included a representation of “Total War”, which was not considered entirely plausible at the time – Wells would continue to argue and warn for its possibility, which turned out to be true. The mass use of poisonous gas became a reality in World War I, the Martian fighting machines, an armoured assault vehicle is like a tank. Inspired by the story, a young Robert Goddard eventually goes on to design rockets that resulted in the Apollo program.

The Radio Play (1938)

The next major iteration on the story of The War of the Worlds was the direction and narration by Orson Welles on October 30, 1938, another item available on Wikimedia, which was the nineteenth show of Welles’ The Mercury Theatre on the Air. Only an hour in length, the radio play re-worked the story by Wells in such a manner to represent a series of live news reports based in the United States, and New Jersey in particular, with updates from other locations around the world. As a narrative progression, the news reports became increasingly alarmist, even if presented in a matter-of-fact manner, as the alien invasion swept aside the resistance of the U.S. military, the end of the first part culminating in the panic and destruction of New York City by poisonous gas, including the death of the radio narrator. In the second half of the show the representation changes to a survivor of the invasion describing the Martian occupation and, as per the original novel, with the Martians dying from terrestrial microbes.

Famously, a modest number of people hearing the news-style episodes of the first part mistook the show for an actual news report, helped by various audio props, and the deliberate suspension of advertising during the broadcast. This format generated some outrage and was considered deceptive by parts of the media, such as the New York Times. Iowa Senator Clyde L. Herring made a call that that radio broadcast programming had to be checked by the Federal Communications Commission prior to transmission. All of this is despite the fact that the script had been deliberately toned down to reduce the realism, especially via changing the names of various locales and organisations. Princeton professor Hadley Cantril in the study The Invasion from Mars (1940), claimed that some six million people heard the broadcast, with 1.7 million believing it was an actual news item. Regards of the veracity of these figures (and the compilation and assessment were highly flawed), the events certainly cemented Welles’ reputation as a dramatist. The broadcast is certainly worth listening to this day, and was followed up on 30 October 1988 with a minor update to the script, the radio show was performed by National Public Radio for the 50th Anniversary of the original broadcast.

The Musical (1978)

The 1978 CBS double LP, “Jeff Wayne’s Musical Version of The War of the Worlds” comes with some evocative, if often lightly detailed, paintings by Peter Goodfellow, with particular scenes from the story presented, appropriately, in the Victorian style. The wrap-around cover, the sinking of the Thunder Child, is perhaps the best of the set, and matched double-sized interior Horsell Common. The interior booklet includes more artwork and the story of the album, narration of the story and songs, as well as biographies of the participants. Richard Burton’s narration as The Journalist is just superb as he navigates the role of being a factual and unemotional reporter among the harsh challenges that he faces. Phil Lynott presents himself very well as the sad and mad, Parson Nathaniel, whereas the difficult combination desperation and calmness of Julie Covington as his wife Beth is a highlight.

As it should be for a story of this scale, the orchestration is nothing short of phenomenal. Most attempts to create “great art” fail in proportion to the incompetency of the artist as such attempts to do show the gaps, but Wayne did produce one of the greatest recordings in history. Starting with the powerful and progressive orchestration of ‘The Eve of the War’, it becomes increasingly ominous with the Martian calls of ‘Ul-la!”, then turning to abrasive conflict for ‘Horsell Common and the Heat Ray’. The incidental music backing ‘The Artilleryman and the Fighting Machine’ remains contextually appropriate. The folksy guitar and pipes combine with the utterly heartbreaking lyrics of loss and love in ‘Forever Autumn’, which are wonderfully expressed via Justin Hayward (and, deservedly, was a top-ten hit in the UK). This returns (as the album often does) to the ominous sounds of ‘The Eve of War’ with the “rout of civilization, the massacre of mankind”, which provides a great lead to the tragic forlorn of hope of ‘Thunder Child’, the last hope and success of humanity.

The haunting instrumentations of ‘The Red Weed’ (parts one and two) are interspersed with the narrative-heavy drama of ‘The Spirit of Man’, which is musically progressive, relentless, and dangerous, although nothing would have been lost with the removal of the guitar solo. As mentioned, Julie Covington’s vocals are astounding and if one is not moved by her desperate plea for humanity, then truly they have no soul. Another heavy narrative section occurs with the hopeless story of the return of the artilleryman Returns in ‘Brave New World’, where the music is really aural wallpaper. As the Narrator descends into a hopeless and lonely madness and makes their way through ‘Dead London’, the sounds are sad, slow, sparse, with the occasional discordant overlay, following by complete silence, before returning to elements of ‘Eve of War’ with the victory of the bacteria. Following this are ‘Epilogue 1’ and ‘Epilogue 2’. The former is somewhat uplifting, with minimal narration, representing a return to life. The second provides a more contemporary narration of landing on Mars then a return ominous music from ‘Eve of World’ providing an uncertain ending.

Such is the success of the album is that there have been multiple re-releases and remixes much of which are, unfortunately, quite lazy and unnecessary, reaching the ultimate level tout inclus for collectors with the seven-disc box set with various unused out-takes and demonstration pieces. Of some special musical value from this collection is the ‘Forever Autumn – N-Trance Remix’. Then there is the 1989 release included an up-tempo and effective dance version of “The Eve of The War” by Ben Liebrand, but minimised the powerful orchestration in the process. In the 2009 version, there is a terrible discontinuity with the album’s narrative with the addition of ‘The Spirit of Man 2009’ and ‘The Eve of the War & Forever Autumn Medley’ tacked on the end.

The Film (2005)

Brief mention is made here of the The War of the Worlds film of 1953 which changed the setting to southern California, with significant reconstruction of the story. The story is overwhelmingly militaristic, the set pieces are improbably squeaky clean, the female roles submissive and weak, and the treatment of religion is nothing short of utterly insulting towards Wells’ secularism. The one redeeming feature is the special effects which were worthy of the Academy Award that was granted at the time. The inclusion of the film into the United States’ National Film Registry in the Library of Congress for significance is certainly over-stating its value.

Minus the definite article, the 2005 film directed by Steven Spielberg, is something that would come with high hopes. After all Spielberg’s ability is provide science fiction and action films in the perspective and involvement of normal people is well recognised (e.g., Close Encounters of the Third Kind, E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial ) and the Wells’ story seems particularly well suited for such a re-telling, and quite clearly that was intended with a story of a working-class American trying to save his children and reached his estranged partner in the midst of an alien invasion. If it is meant to be a story of personal redemption through familial loyalty (the wife’s new partner faces an inevitable disappearance) there is little evidence of such character development; perhaps the lead actor was type-cast.

The film makes a number of plot liberties from the book, which of course is necessary and acceptable. The thematic changes are less so. A seriously weird convergence occurs with the astronomer Ogilvy from the original book, the madness of the pastor, and the grand ideas of the artilleryman. The character and the scene are quite evocative, as is the frightening capture that follows, the loss of thematic content is less useful. There is some good in the film; the scientific modernisation is necessary (although flawed with the magical digital video recorders, and the buried aliens who could have taken over at any time previous), the behaviour of the mob was indicative of failed individualism, the desperate attempted ferry crossing across the Hudson and the genuinely frightening. But overall it doesn’t hold a candle to Wells, and is one of the bottom-rung films directed by the usually more competent Spielberg.

As a nominal music site, comments must be made of the score by the veteran composer John Williams. This is quite difficult to review in a way due to the extremely competent, but also lucklustre content and delivery. Throughout there are movements when are atmospheric, often ominous, with excellent use of instrumentation, such as the violins in ‘Reaching the Country’, the cello and drum in ‘Probing the Basement’, the piano pieces in ‘Refugee Status’. It’s all rather reminiscent of the soundtrack in Jaws, especially, and to a degree Lord of the Rings, but there is no sense of real development in the score. From all accounts John Williams tried very hard

Other Cultural Products and Our Context

In addition to these well-known contributions to what is a continuing cultural product there are several others which bear the title which must at the very least receive some mention. A personal favourite must be The Great Martian War 1913–1917, an faux documentary and alternate history of World War I which weaves actual events of WWI in its tale with expertly produced footage in the style of archived information. The incorporation of the effects of the Spanish ‘flu to the narrative, and a surprising plot twist makes it an absolutely worthwhile item of intelligent entertainment. Also extremely worthy of viewing is the contemporary television series War of the Worlds/La Guerre Des Mondes, which also has very little to do with the H.G. Wells’ story but combines British realism with French imagination, providing realistic and flawed characters in desperate circumstances. In addition to these, there are multiple direct-to-DVD and TV series, several video games, and a large number of associated publications.

Today, instead of the microbes being the saviour of the species in our times they’re a challenge to our species-survival. Yes, there is ill-informed talk about a potential vaccine, perhaps even next year. Recognising that no vaccine has ever been developed for any sort of coronavirus, at this stage it seems that the vaccine will only be partially successful, conferring a rather low rate of immunity, perhaps around the 65% mark, which will be too low for standard rates and behaviour that provides herd immunity. A systemic process of elimination, and re-elimination when necessary, seems to be the only possible path for eventual success against the virus under current circumstances. To draw back into an aesthetic dimension (given the nature of this site) for the lay epidemiologist with cultural knowledge, it is best to think of this as one of the many examples from the genre of zombie films. How ironic are Wells’ lines following the death of the Martians; By the toll of a billion deaths man has bought his birthright of the earth, and it is his against all comers; it would still be his were the Martians ten times as mighty as they are. For neither do men live nor die in vain.

Birthright of the Earth??

By fighting etc??

Puerile thought.

“MAN” (!!!) certainly does not have entitlement, birthright or any other – right – to this earth/planet.

Only responsibility to leave it as healthy as it was when ( “HE!!) appeared on it.

Surely this is one of the sources of all our present ecological/environmental problems?

But really appreciate this collection you prepared.