“It’s like an evil genius cloned Stock, Aitken & Waterman by dark magic and animated them with bitterness and despair” — Rayner Lucas.

Your pop favourites and mine, Jenny McLaren and Ricardo Autobahn of Spray, have an exciting new single out! It’s “The Big Idea” from their album Ambiguous Poems About Death, remixed and sped up!

That’s the three-minute single video — but you should play the one-hour hyperextended mix while you’re reading this.

That’s the three-minute single video — but you should play the one-hour hyperextended mix while you’re reading this.

It’s a remarkable remix — it works like a 12” remix, it has a proper structure and doesn’t just sound like the same six minutes ten times.

Tim Burgess is doing a Twitter Listening Party for Ambiguous Poems About Death tomorrow, Friday 12 May, at 9:00pm UK time (UTC+1). Be listening in! Tell your friends!

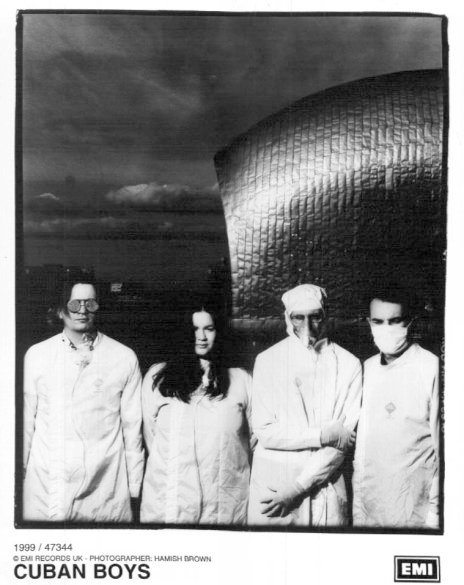

I chatted about the single, the band and their former incarnation as the Cuban Boys with Ricardo Autobahn.

“I’m a big fan of single versions. The one that springs to mind immediately is ‘Suburbia’ by the Pet Shop Boys. If you listen to the album version of ‘Suburbia,’ it sounds like a demo compared to the single version.

“Radio mixes, airplay edits, I’ve always been a big fan of cranking it up to 110%. ‘The Big Idea’ on the album was a fan favourite, so tweaking it for a single release seemed like a no-brainer. It seems to be our most streamed song on the assorted platforms.”

The extended remix of “The Big Idea” goes nearly an hour. Why?

“Back in 2010, we were going to do another album. But we realized there’s no need for albums any more because of streaming, it was iTunes then, there’s no format limit. You didn’t have to fit an album on a CD, so you could just do what you like.

“I like the idea of not being limited by the format any more. An album could be six days long if you want. Everything is limited by technology — the seven-inch single to the vinyl album to the CD, all records, all art, has to be concerned with that. This led me on to thinking, what could you do with a twelve-inch mix if you weren’t limited by the fact you could only get twenty minutes on the side of a slab of vinyl?”

The actual limit nowadays is not technical time limitations, it’s how do you hold their attention?

“By making a song that’s an hour long just to attempt to increase your footprint. Everything Spray does, we always try and think of a way to increase our footprint even if it’s microscopically, as long as we’re just doing something to get people interested.

“Doing a a sixty-minute mix is an artistic decision, but it’s a gimmick decision as well. It took a couple of days. The seven inch mix was already there, so it was a case of just taking the blocks and spreading it out.

“You take the song and you spread it out. You start with the kick drum, you build the drums up for two minutes so that the DJs have something to mix into, you go to the end of the song and spread the drums out for two and a half minutes so that the DJs have something to mix out of, and then you jiggle around the bits in the middle until it’s roughly what whatever the fashionable length of time is these days. It’s getting shorter by the year.

“So when we did the 120-inch mix, we started with the drums and just saw how long we could slowly build up the drums until it becomes intolerable, and it was five or six minutes. I thought right, let’s drag the bass line across. We never use one sequencer part, we always use four sequencer parts that we blend together, so bringing each one of those in very slowly also gave us five or ten minutes just to play around with. So we got to fifteen minutes before we even thought about a vocal.

“There’s a lot of crashes and splashes and explosions throughout the song, and they were largely there so I could tell where each section of the song was. Every time there’s a crash and explosion it was partially so that when I was looking at it on the screen I could tell if this was verse 42 or instrumental break 112.

“If there’s one thing Spray are excellent at, it’s our drum fills. If there’s one thing we should be remembered for, I’d like it to be the drum fills.”

I actually heard the long mix first and then heard the short mix. It’s a banger, a perfect little jewel, it’s a seven inch.

“It is, and if there only wasn’t so much backlog at the pressing plants, I’d have had one made just for the LOLs. But the 120-inch mix, a friend of mine played on his radio show a few weeks ago. When I listened to it as a passive consumer, I did think there were a few things that would change. There’s a bit around forty-five minutes where it gets a bit boring. There’s an instrumental break, it sort of dips so it can come back to the last chorus, I think I may have just dragged that out a bit too much.”

Nah, I think it works in context: you’re listening to an hour-long remix, and if you’ve made it to the forty-fifth minute you’re already well in. Has it been played in an actual disco anywhere on Earth that you know of?

“Not that I know of. These things tend to float in at least two months after the event. If it becomes a big club hit, I don’t know at the time, people tell me months later.”

For the single video, you just got the previous video and cut it up a bit faster. Do you make your videos yourselves too?

“All those videos are done in our parents’ dining room. I just put a green screen up, we dick around for ten minutes until we get bored, and then stick it in the Mac and see what comes out, just throw every effect I can find at it.

“Very little is done by outside forces when it comes to Spray. The art is other people now, and we’re getting other people to mix them because I hate mixing records. That’s why our records are sounding a lot better in recent years.”

You did a seven inch few years ago, “Félicette, Space Cat.” What sort of logistical nightmare is it doing a seven inch in the modern era?

“It wasn’t too bad. This was 2021, so it was just before everything went tits-up with the pressing plants. They quoted me ten weeks, it ended up being fourteen, and then almost immediately after that everybody was having to wait a year for their records. All the pressing plants are in Czechoslovakia, and Record Store Day has suddenly become really popular. There’s a new pressing plant in Newcastle I think [Press On, in Middlesbrough], they’ve started doing stuff for indie labels, and I might give them a go with with some crackpot project.”

What are sales like for a band on Bandcamp these days? How many people throw money at you for records?

“It’s not a living, Spray can’t do more than about a couple of thousand pounds a year. As a side hustle, it’s fabulous. When big names use Bandcamp, like Radiohead or whatever, it legitimizes the platform. Bandcamp always has a certain feel that you’re just duplicating your own tapes and selling them out of the back of a car.”

And the artist actually gets paid.

“Oh yes, that’s amazing, exactly. And it comes through immediately as well, you don’t have to wait six months for it. If I sell a couple of Cuban Boys CDs in the morning, oh, there’s a nice bit of money in my PayPal, lovely stuff.”

CDs and records are just T-shirts these days, they’re souvenirs.

“That’s why when we did the ‘Félicette’ picture disc, there’s not a lot of text on it, because I thought it would look really nice sitting on somebody’s wall. That was the first thing we thought of when we designed the artwork.”

I’m just amazed these formats even exist as possible any more.

“Oh yeah yeah, you can even get minidiscs pressed up. I keep thinking of getting a small run of twenty minidiscs of the album. The cover versions album that we did last year, that’s going to come out on CD in a couple of months’ time, so I’ll get twenty minidiscs pressed as a sort of companion.”

A £200 laptop does more than you could do with a studio in the eighties. You listen to old industrial records, you wonder how the hell they did that with what they had.

“This is going back to 1999 when we did the Cuban Boys album. We drove two hundred miles to the studio, my rental car full of huge bits of kit, a gigantic sampler, my laptop PC, two synthesizers, to record an album in Wales which could be done by email nowadays. That entire car journey could be just me sending files. I can’t imagine how complicated it was making technological electronic music in the eighties when you didn’t have computers, when you were pushing buttons and actually using cables.

“The thing about the eighties, everybody was trying to sound the same, but with completely different equipment. That’s why you end up with such interesting pop music. Nowadays everybody’s trying to sound the same, and they’ve all got the same equipment, the same plugins.

“There’s a number of Fairlight presets on the Spray album because they’re classic tropes. That Fairlight ‘womp’ orchestral hit, and the ‘aaaaaah’ from ‘Moments In Love.’ They’re the two gimmicks that we always use, because they reference the eighties without being too specific about it.

“Going back to the late nineties, the Cuban Boys, we made a point of never using the presets, we tweaked it slightly. Artistically, we felt we had to do it. You think, we can’t use the main one because somebody will know it’s the main sound, they’ll laugh at us! But nowadays, that studio computer, there are so many plugins, so many synthesizers, that the worry that somebody will know what I’m using and laugh at me, it goes away completely.”

Also, no-one was going to listen to you and laugh at you, they just wanted to hear a banger. When you fox yourself by being just a bit too smart.

“That’s probably the story of Spray. Too clever for this world. I was doing an interview about novelty records about a week ago, and I posited the theory that everybody who makes a novelty record is actually cleverer than people who make normal pop records, because they can’t bring themselves to dumb down to basic ‘I love you baby’ lyrics, so they do these strange weird experiments that turn into gimmicky chart novelty idiocy.”

You get a satirical band like This Is Serious Mum.

“God, I love them so much, and nobody knows them up here. If you get TISM, they’ve got the platform, they’ve got the ideas, but they’ve also got a sense of pop music as well. There’s people I love like the Residents, who have a platform and a brilliant image and loads of ideas, but the Residents never really cared about pop music. Very few people in the arty side of things are really that bothered about hit records. The people in the arty side who do care about hit records often make the best hit records.”

Leave a Reply