I won’t try to explain the entire saga of the Sad Puppies and their Rabid Puppies offshoot. But in short, a bunch of reactionary science fiction authors were upset that people other than white straight guys were getting their stories noticed, so started a backlash to take over the Hugo Awards through slate voting, and made stupendous dicks of themselves. The Wikipedia article is mostly confusing, but Wired last year and The Guardian this year give an overview.

The thing that really struck me about the Sad Puppies — and it’s something I haven’t seen anyone else note — was Puppies founder Brad Torgersen’s lament that he could no longer tell from the cover of a science fiction novel what it was about, like he could “a few decades ago”. No, really: a grown man who purported to write books for money lamented that he could no longer literally judge a book by its cover:

The book has a spaceship on the cover, but is it really going to be a story about space exploration and pioneering derring-do? Or is the story merely about racial prejudice and exploitation, with interplanetary or interstellar trappings?

I thought “you knob, you didn’t buy a book at all in the seventies or eighties, did you.”

Do you not remember how generic the art on seventies SF paperbacks was? It might have a space station on it and actually be completely earthbound. An Asimov about bureaucratic political intrigue in a single room — frequently, like most science fiction ever, a thin allegory for something entirely contemporary — would have a cover with spaceships shooting curiously visible energy beams at each other. This is assuming they didn’t take a straightforward space story and shove a psychedelic fever dream on it that the artist hadn’t been able to sell to a prog rock band. (Art went in both directions between SF/F and records in the day.)

Quite often, the publishers bought the art in separately and slapped it on any book that happened to need a cover that month. (At least Panther had Chris Foss on tap.)

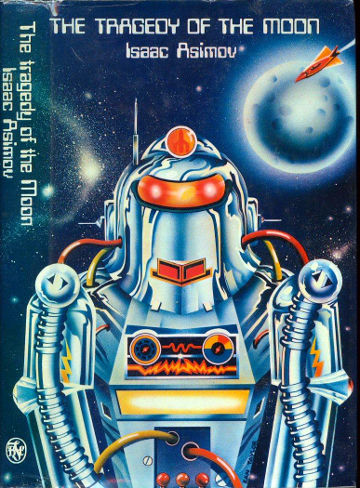

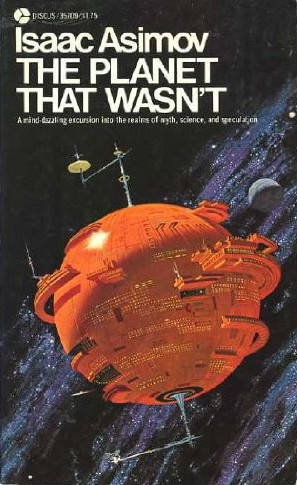

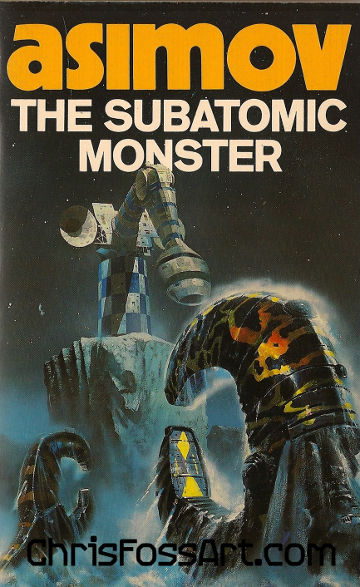

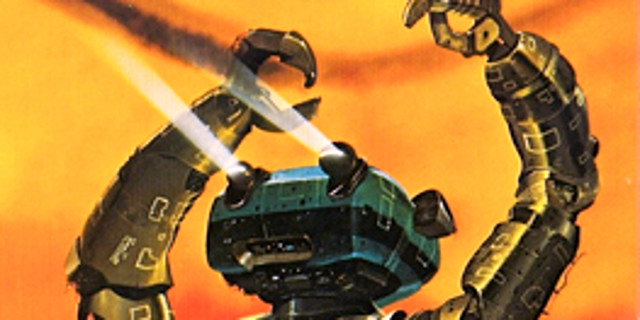

And then there were the Asimov non-fiction science fact books with giant robots on the cover:

|

|

|

Asimov popular science essay collections, none of which featured science-fictional robots. And no, the planet in question didn’t turn out to be a space station.

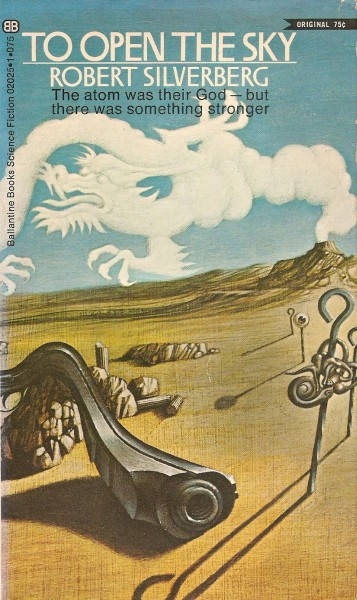

The covers never had any relation to the contents. They might as well have been labeled “extruded SF product”. No publisher ever thought “accurately representing the content of these books is job number one”; they thought “what will sell copies?”

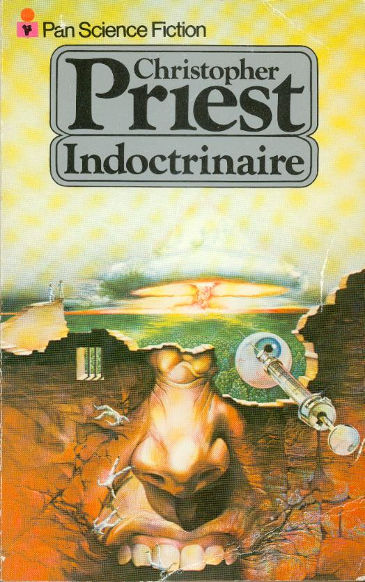

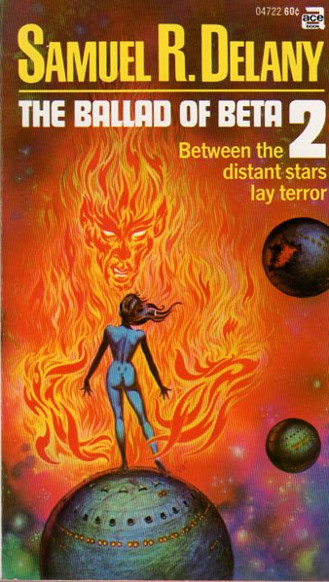

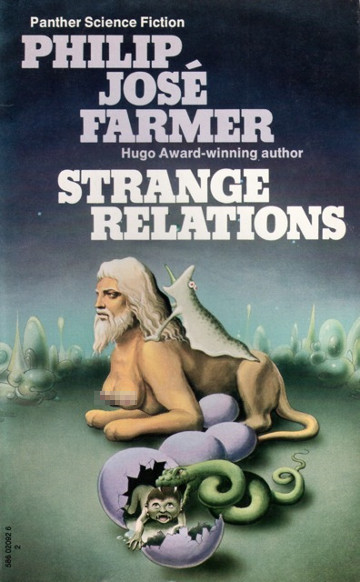

Don’t take my word for it. Look at this shit. If you think I exaggerate, I want your summary of each of the books at that link purely from what you can see right there.

|

|

|

|

It was the seventies. The drugs were just part of how people did, uh, everything. As were tits. Here’s the unpixelated version of that last one, as found in newsagents in 1973.

The Sad Puppies’ particular backstab myth extended to this degree of just making shit up. And they wonder why everyone hates them.

edit: this is popular, isn’t it. If you like this article, please feel free to grab me a coffee.

> Do you not remember how generic the art on seventies SF paperbacks was? <

Shit yes. Someone needs to dig through their collection and pay a little bit of attention.

Oh very nicely done.

No, Lev, That Someone actually needs to actually read some scifi. But that would require being able to read. Not a top priority for Sad Puppies.

The puppies are so afraid that there will be science fiction books that contain ideas. Ideas are pretty much central to science fiction. But the puppies aren’t really against ideas, just against ideas they don’t like. The kind of books they like are the ones where everything stops to the main character can deliver a long political lecture. The difference is that no one is trying to squash the books the puppies like. It’s just that not that many science fiction fans share their taste in books.

Hey, how about those Dragons!!!!!

Now, now. Michael Whelan at least read the books he illustrated. His covers for Jo Clayton might feature Aleytys in the all together but the scene he used would always be in the book.

Not sure why his cover for Friday had little penis zippers, aside from “because they could.”

fellow filer here.

Illustration in the 60s-70s (maybe even the 80s) was definitely a case of “it’s SF, put something that hints at SF, or the strange/weird on the cover”.

But I don’t think that the puppies disconnect is all about the cover art: I also think it is about the “age of reception”.

We’ve all heard that saying about the golden age of SF being ten, or 12 or…referencing the age of the reader at the time of discovery, as opposed to some great lost age when EVERYTHING was better than it is now.

So here’s my take: puppies, as readers, stopped evolving (or lack the capacity to evolve) beyond those formative years when they read at the surface only: the invasion of Earth was just a cool invasion with nasty alien creatures out to suck our blood – not a missive on the dangers of colonialism.

I must confess that it takes an act of will for me to put on my critiquing hat when reading SF – but I learned how to do it in high school and college and, if required for the discussion, I can uncover the meanings behind the prose, the ways in which something relates to the modern day (or era the novel was written in).

I don’t think puppies can. Or maybe only to a limited degree (Chekhov was a stand-in for Communist Russia = we turned the bad guys into good guys) -or, perhaps worse, believe that such delving into deeper meaning is somehow an SJW trait. Or maybe they are just lazy and think the words allegory and metaphor have too many syllables.

I recently read a sociological piece at Mother Jones – I spent Five Years with Trump’s People or some such – where the author essentially stated that the people who buy into Trump are generally less educated and have the sense that the future is leaving them behind. They can’t natively parse most higher-level discourse, and it’s therefore received as the “elites” having one over on them by talking in confusing terms. Their worst trait is suffering from the Dunning-Kreuger effect: they’ve no idea how ignorant they are and are incapable of recognizing that it is their lack that causes the problem, not necessarily the outside world.

Given the bleatings about “message fiction” that weave in and out of puppy blatherings, it’s a good possibility that this is in operation for puppies just as much as it is for Trumpies.

And the getting left behind resonates quite closely: the interviewees expressed hate for “immigrants who get all kinds of support – what about me?”: the puppies are saying “the immigrant (women, POCs, LGBTQ) authors are getting all the awards, what about me?”

I dunno, I think given the Brexit voters, AfD and the people who voted for Tony Abbott, I think we have to not necessarily excuse it as stupidity or lack of education, and consider the possibility there’s a non-negligible constituency of just plain vicious arseholes.

I well remember the UK’s age of non-relevant SF paperback covers, because I was the paperback stock buyer for a general bookshop in the late 70’s–early ’80s (as well as an assiduous reader/collector before and since). The UK book industry assumption then was that any sf paperback would sell at least 20,000 in the UK/Commonwealth market, anything competent would sell up to 40,000, and anything good would hit a ceiling of 60,000 – only novels (but likely not collections) by the long-established or rare breakout authors like Asimov, Clarke and Herbert were expected to sell more and join the permanent backlist. The assumption – probably correct – was that there was a core of fans (like myself) who would buy anything in the genre, but reaching beyond them was hard, and success in doing so hard to predict.

This meant that SF and Fantasy was worth publishing in paperback, but on average not worth putting much extra effort into. Occasionally a particular new author like Stephen R Donaldson would get a big marketing push, but this was rare. I remember particularly that the runaway success of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy came as a surprise to Pan. (Though not to me, and I tried to tip them off via their Rep – several of the Publisher’s Reps used to visit me early in their monthly tours because, as a fan who read the US magazines, I could often tell them more about their forthcoming SF/F titles than their own marketing department!)

On this basis, the most important feature of the cover was the author’s name, which most target buyers would recognise. As the article makes clear, indication of a science fictional or fantasy nature was also expected (and this could be some what Abstract as other genres didn’t use that style), but cover representation of the specific content was considered optional by most UK pbk publishers.

Back then one saw US-published SF/F in the UK much less frequently (there being half a dozen or less bookshops in the entire UK that would, semi-legally, import them). However, from those I did acquire, I gained the impression that US covers in the same era were much more often representational of the actual story contained therein (but *cough* Richard M Powers *cough*).

If this is true, then the adherents of the mostly-US Puppy movement(s) might genuinely be remembering different and more representative covers. Conversely, I’ve seen much comment around the blogs to the effect that their most vocal spokespersons are too young to have actually been reading SF/F in this purported “golden era of representational covers” whose passing they bemoan. (Arguably, they may have been reading their parent’s old copies, but I’ve never got that impression from them.)

Can someone knowledgeable about 60’s–80’s covers from both sides of the Pond speak to this?

Can’t say I’m knowledgeable about it – as a teenager in the ’80s in Australia most of what I got was UK printings with a few US – but I note that quite a lot of the stuff on both Sci-Fi Book Art and Good Show Sir, including two of the four in the bottom cluster above, came from the US. They appear to have been every bit as weird at the time.

One of Anne McCaffrey’s short stories, “Weather on Welladay,” was written by the method of “the publisher showed me what the magazine cover art was going to be and asked for a story to match.” (She mentions this in the foreword to one of her collections.) So if one were to use that story as an example of being able to tell what the story was about from the cover, it would be putting the cart before the horse.