“I don’t listen to music. It’s a blind spot.”

I started reading J. G. Ballard in earnest way back in Perth. I’d read “The Voices Of Time” in Spectrum 3 in my early teenage second-hand bookshop fueled SF paperback binge — the quintessential Ballard drained swimming pool story — but didn’t get heavily into him until my early twenties, deep in rock critic angst and Perth ennui. It was when I read the Vermilion Sands collection that it became clear: Perth is Vermilion Sands made flesh, and coming from there is like growing up in a holiday resort out of season.

And of course the Re/Search Ballard issue, and The Atrocity Exhibition, which is as close as you’ll find to hideous screeching noise music in written form. (The entire first edition was shredded by its publisher before release! You don’t get a tribute like that for free.) I treasure my copy of the fancy 1990 illustrated edition, with the explanatory footnotes you’ll find in the present paperback. Going down the park on a Saturday afternoon, sitting on a bench amongst the greenery, watching the ducks and reading about Traven painstakingly assembling JFK assassination dioramas and slowly losing it.

Part of the new wave of science fiction in the 1960s, Ballard framed the point of view for the whole of the new wave of music in the 1970s. He’s all over punk, post-punk, ’80s chart synthpop and industrial, to this day. Music press articles on his influence are a staple — here, have a wide-ranging survey from 2009, and a less rigorous one (the name “Daniel Miller” never appears) from this year. It’s Ballard’s musical form, we just get to listen to it.

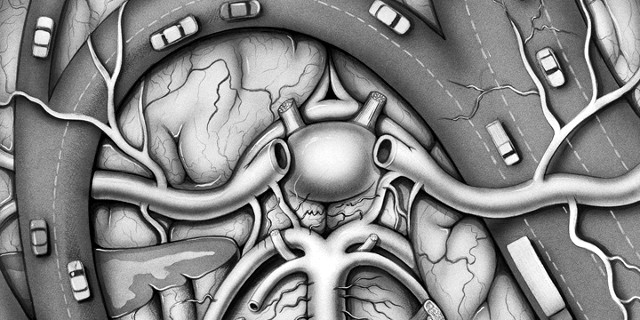

The power is in Ballard’s imagery. The adjective “Ballardian” is not so much about his verbal style (though that too), but the rapid-fire images he projects onto your mind’s eye. His characters tend to the cardboard at best (variations on increasingly unbalanced middle-class suburban English scientist Dr Richard Traven and his even less substantial photocopy cutout wife or girlfriend, with the occasional spectacular lunatic like Vaughn from Crash), but his way with a striking written image is the quintessence of lyrics. And if you were keen on writers like the then-obscure Burroughs, Ballard’s clear and clinical tone — he studied medicine, he edited on a chemical industry news magazine, his friend Christopher Evans gave him all his technical junk mail for inspiration — was like a brilliant crystal, sharp enough to use as a weapon. And shape you into more of itself.

The best part of this is that he had essentially zero interest in music himself. He preferred silence while writing, he often watched TV with the sound off (it’s all about the flow of imagery), he seems never to have bought a record in his life and he got his girlfriend to help him pick records for BBC Desert Island Discs. From The Paris Review, Winter 1984:

INTERVIEWER

Speaking of the media landscape, you don’t seem to mention music very much. What do you listen to?

BALLARD

I think I’m the only person I know who doesn’t own a record player or a single record. I’ve never understood why, because my maternal grandparents were lifelong teachers of music, and my father, as a choir boy, once sang solo in Manchester Cathedral. But that gene seems to have skipped me. I often listen to classical music on the radio, though never as background. I can’t stand people who switch on the record player as soon as you arrive for drinks. Either we listen to Mozart or Vivaldi, or we talk. It seems daft to try to do them together, any more than one would hold a conversation during a screening of Casablanca. In fact, without thinking I usually stop talking altogether, waiting for the music to finish, to the host’s puzzlement.

He was interested in music video, apparently being quite keen on David Bowie’s video for “Ashes To Ashes”:

Simon Sellars notes:

Ballard may claim there’s no music in his work, but there certainly is an attitude, a postpunk, posthuman sensibility — a cool irony providing the backdrop for an ambiguous, detached protagonist, a cipher who may or may not be seduced by the unleashing of technology’s dark side.

Really, it’s technology — the media landscape; the urban sprawl; the self-regulating, self-sufficient cityscape — that’s the main character in much of Ballard’s work, so it’s not that hard to see the appeal of his world view to a bunch of callow, early 80s non-musicians living in the shadow of the urban wasteland with just their synthesizers and reel-to-reel tape decks for company.

(You may also enjoy Simon Sellars’ Ballard playlist on Spotify.)

Ballard himself notes in NME in 1985:

Punk was so interesting — I still haven’t recovered from it. Not knowing anything about the music I saw it as a purely political movement, the powerful political and social resentment of an under-caste who reacted to the values of bourgeois society with pure destructiveness and hate. Bourgeois society offered them the mortgage, they offered back psychosis.

Sadly, there’s not much in the way of songs about Ballard. Though Dan Melchior sings of living in Shepperton and accidentally shadowing Ballard through his day. Jim got all the frozen peas first.

Leave a Reply